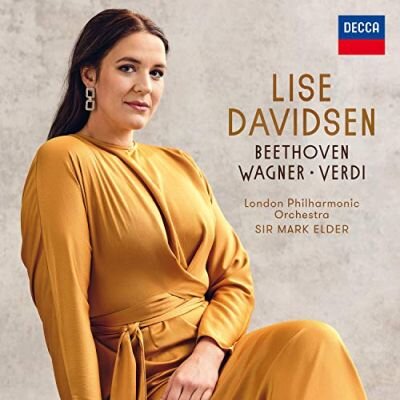

Lise Davidsen’s debut album—with Strauss’ Vier letzte lieder as centerpiece—was met with ecstatic critical praise last year. It all went over my head, however. She sounded mannered to me, hooty, with an unpleasant hollowness to her tone. For somebody already being compared to the likes of Kirsten Flagstad and Birgit Nilsson, her voice was less than expected. So I was less than thrilled to hear this disc when it arrived. Who wants to hear another earful of an artist who may not be quite ready for the world stage? But how wrong I was this time around!

The voice that poured out from my speakers was opulent, warm, secure, with a glint of sunniness to her middle and top registers. How nimbly and naturally she can wield her instrument was immediately apparent in her reading Wagner’s Wesendonck Lieder, the heart of this disc. With a flexibility that is nothing less than astonishing, she deftly turned from strength to vulnerability and back, sounding as if she were born to inhabit this quietly anxious chromatic music (to say nothing of the female lead in the opera this score was a test-run for). “Im Treibhaus” is rent with unfulfilled passion verging on heartbreak, which leads into a “Träume” that is as dreamily ecstatic as I have ever heard; a release of breath, desire which Davidsen conjures a miniature “Liebestod” out of, vanishing into the air of a spring night. The expanse of feeling she conveys between “Daß sie wachsen” to “Und dann sinken in die Gruft” defies efforts to pin down in mere words.

Davidsen sounds no less at home in the excerpts of Cherubini, Verdi, and Mascagni which fill out this recital. Her evenness of tone, the suavity which her voice modulates registers, and her impeccably controlled pianissimi in “Pace, pace” from La forza del destino, for example, is the kind of feat which few sopranos active today could match. None could surpass Davidsen. Her “Ave Maria” from Otello is another superb display of vocal virtuosity and minutely calibrated emotional power.

My impressions of Davidsen were so sharply divergent from what I heard in her previous Decca disc, that I fished it out to relisten and compare. Maybe I was wrong back then too. But, no, the same problems I had with that recording remained. Perhaps she was feeling more tense, less trusting of her formidable instincts and talents. What is certain is that Esa-Pekka Salonen, a superb musician, was simply the wrong choice to accompany Davidsen on her debut. His emotional aloofness and clipped phrasing are deadly in Wagner and Strauss. For the most part Mark Elder is a much better partner, although there are moments when one would have preferred that he had given Davidsen just a little more give with respect to tempi.

Make no mistake—these are very minor complaints which, in the face of Davidsen’s achievements, are insignificant. My hope is that she (and her handlers) carefully stewards her voice and builds upon the foundation which is her birthright. Is she really the next [enter your choice of Wagnerian prima donna of the past here]? I cannot say. What I do know is that she is a very remarkable Lise Davidsen right now; capable of earning the respect she merits without relying on cheap marketing hyperbole. Long may this artist continue to thrive.